Can the COVID-19 Pandemic Save Other Lives?

July 8, 2020

Associate Director UCONN Health Disparities Institute;

President, Health & Technology Vector; member of Donaghue Greater Value Portfolio Review Committee

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to rage across the country. The death toll just surpassed 100,000 in less than 3 months, the same number as the annual deaths from medical errors reported in the 1999 Institute of Medicine landmark publication “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System”. Other studies put the number of premature deaths to be as high as 400,000. Understandably, all the attention has focused on the dreadful toll of the pandemic and on the heroic efforts to save lives and contain its spread. So far, there has been no attention paid to any incidental health benefits, including mortality rates, of the pandemic perhaps because there are no examples in modern history when we have experienced such a sudden, widespread and long-lasting vanishing of non-emergency health services. Now it seems reasonable to ask the following questions: Has the pandemic precluded access to harmful procedures? Could this natural experiment tell us more about high and low value services by their absence rather than by their presence? Could proportionately greater benefits accrue to racial ethnic minorities who in “normal times” experience 20% higher mortality than whites from certain surgical procedures? Could the pandemic be unwittingly saving other lives? Whose lives? By what specific acts of involuntary omission or well-intended commission? Have medical errors vanished alongside medical miracles?

This essay will not answer these questions but will offer an approach and possibly a methodology to delve into the matter. An intriguing proxy for our current situation could be found in studies of physician strikes, work slowdowns and other voluntary absences on mortality rates across the globe and in the US. However, physician strikes are extremely rare, ethically frowned upon and even illegal in many countries. That makes the research challenging; it requires a sufficiently large sample and reliable sources of data to venture statistically valid answers.

In June of 2000, an article in the British Medical Journal entitled “Doctors’ strike in Israel may be good for health” is both tantalizing and counterintuitive. The article showed that death rates had dropped significantly, as measured by funeral homes statistics, after the Israel Medical Association launched a strike to protest against a government proposed four-year wage contract for doctors. The 3-month strike resulted in the cancellation of hundreds of thousands outpatient visits and tens of thousands of elective surgeries. Only essential services such as emergency rooms, dialysis units and maternity and neonatal services remained open (not unlike the current situation in the US). The Jerusalem Post, an Israeli newspaper surveyed non-profit Jewish burial societies, which at the time performed most of the funerals in the country. The number of funerals had, paradoxically, dropped significantly. One burial society director recounted “This month, there were only 93 funerals compared with 153 in May 1999, 133 in the same month in 1998, and 139 in May 1997”.

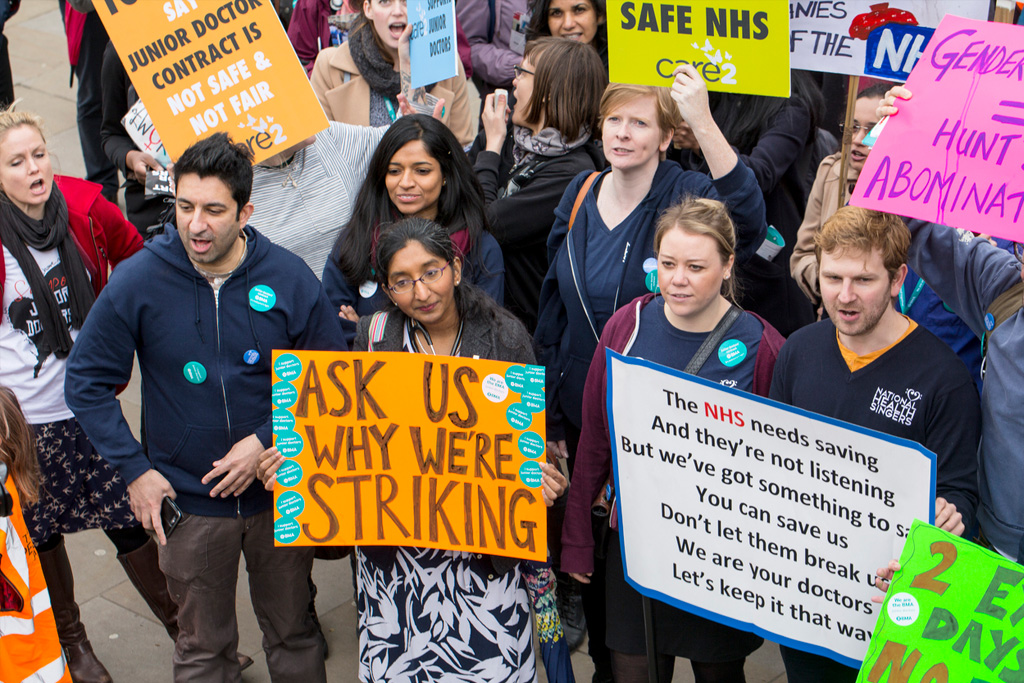

In another case, doctors in London went on a series of strikes, each lasting 48 hrs. or less between January and April of 2016. Doctors were protesting against proposed changes in compensation and working conditions by the National Health Service (NHS). The public was understandably concerned about the negative consequences of such extreme measure. In an attempt to harness public support for their position the NHS voiced fears that a work stoppage would result in patient deaths. A subsequent analysis showed that the strike, including one that shut down emergency services had “a significant impact” but it did not result in an excess number of deaths. This can be explained by the short duration of those strikes and the fact that these were “Junior doctors” the designation for recent medical school graduates who are undergoing post graduate work.

In 2008, a team of researchers at Emory University led by Dr. Solveig J. Cunningham performed a systematic review of physician strikes on mortality rates throughout the globe. Dr. Solveig’s team studied five strikes, all between 1976 and 2003 including one in Spain, Los Angeles and Croatia and two in Israel. The strikes or slowdowns lasted between 9 days and 17 weeks. In most cases emergency room, delivery rooms, neonatal units and other essential services remained open. When compared to mortality rates at other times, none of the strikes showed an increase in mortality.

In the case of the 1976 Los Angeles strike protesting against increases in malpractice premiums, 50% of physicians in the county cut back on their scope of services. An analysis of its impact on mortality estimated that between 31 and 132 deaths could be attributable to the strike while 55 to 153 deaths were avoided due to the strike. Even though the differences were not statistically significant, the author hypothesized that the reduction may have been due to fewer elective surgeries. This hypothesis was later reinforced by studies looking at mortality rates shortly after the strike because surgical mortality sometimes occurs two to three weeks later. Moreover, delays in reporting deaths during the strike would undercount strike-related deaths. Death rates during up to 7 weeks after the strike was also lower compared to the average mortality during the same period in the previous 5 years. In comparison, infant mortality, a reliable indicator of population health showed no significant changes from previous years. In the case of the longer Israeli strike of 1973, death rates declined by 50%. However, other studies found no significant differences in the number of deaths associated with a subsequent strike involving 8,000 of 11,000 Jerusalem physicians in 1983.

Another interesting study showed that patients with high-risk heart conditions who are hospitalized in academic medical centers while cardiologists are absent attending a professional meeting experience lower cardiac-related mortality rate.

These studies may be the closest proxies we have to understand the potential consequences of the dramatic reduction in the number of services available to the public during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly a reduction in elective surgical procedures. Since randomized studies that assign people to “no care” or “postponed care” on a massive scale would be both unethical and infeasible, we should turn our attention to the unfolding natural experiment to find answers to all our questions. We may learn valuable lessons about value in healthcare.

Back Issues

Developing a Research Agenda on High-Value, Equitable Care: The Power of Being Practical, Inclusive, and Innovative

The Room Where Research Happens: How I Became Part of a Group that Was Open to Research the Topic that Few Seemed Willing to Discuss