Seeking a (more) perfect approach to social risk adjustment

November 4, 2025

Accurate risk adjustment is essential for value-based payment. While the concept is straightforward—outcome accountability in payment models requires estimating anticipated costs of care for different patients—the methods for calculating risk adjustment can be intricate. For instance, if risk adjustments lead to cost estimates that are too low, because they do not account for how sick or complex a population may be, clinicians and organizations in value-based payment models can unfairly incur financial losses when taking care of that population. If cost estimates are too high, payers unfairly incur losses for spending in excess of what healthcare providers need.

The goal for risk adjustment is to balance these dynamics and estimate anticipated spending as closely as possible, allowing payers and providers to interact in ways that support greater health and cost-efficiency. The need for strong and appropriate risk adjustment is particularly important for population-based payment models such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), which involve clinicians and delivery organizations assuming total cost accountability for defined populations.

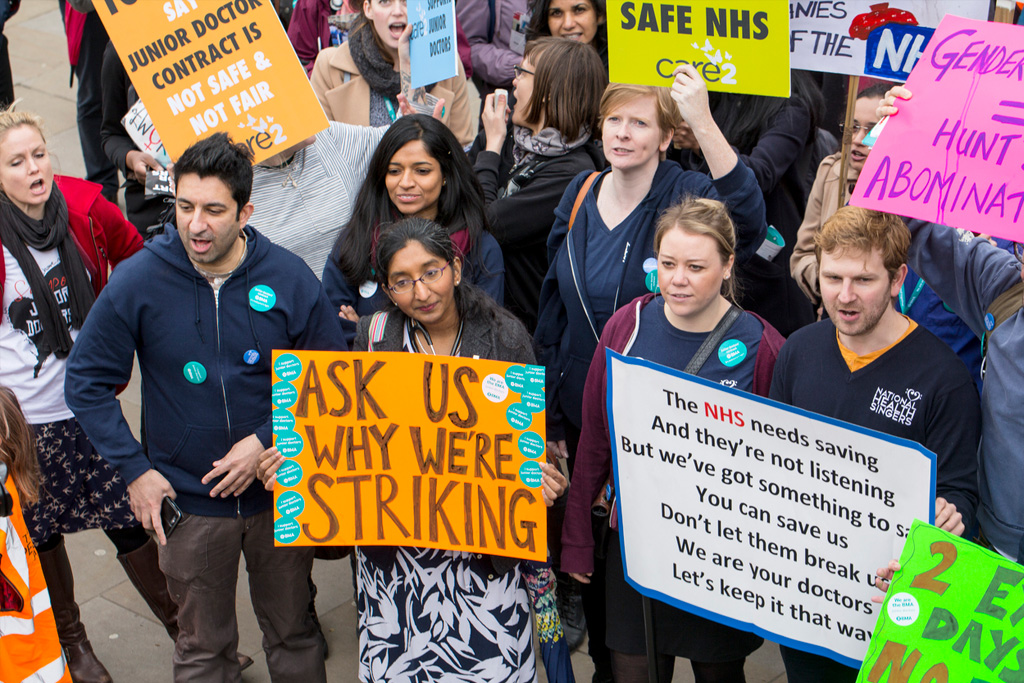

Improvement in this area is urgently needed, particularly for safety-net organizations that care for populations with high social needs. Traditionally, risk adjustment has focused on patients’ clinical diagnoses that can affect health care costs, but not social factors that can also affect health and make health care costlier to provide. Risk adjustment has therefore underestimated benchmarks and payments for safety-net organizations, leading to either exclusion and departures from payment models—or within models, disproportionate financial penalties that further strain their financial health.

With support from the Donaghue Foundation, our team has conducted research supporting the potential benefits of additional risk adjustment on the basis of social needs—social risk adjustment—in population-based Medicare ACOs. Yet policymakers need guidance on the most promising approaches to social risk adjustment.

Current approaches to social risk adjustment

Strategies for social risk adjustment may vary between different payment models. In the case of ACO REACH, social risk adjustment modifies beneficiary-level spending benchmarks according to two factors: 1) whether a beneficiary is dual-eligible for Medicare and Medicaid or eligible for the Low-Income Subsidy, and 2) whether the beneficiary resides in an area with high or low socioeconomic disadvantage, initially assessed by the Area Deprivation Index. Monthly benchmarks can increase by up to $30 for beneficiaries living in the most disadvantaged areas and decrease by $10 for those living in relatively advantaged areas. Medicare recently adopted a new measure for determining socioeconomic disadvantage, the Community Deprivation Index, which sought to address methodological problems with the Area Deprivation Index.

Our team has examined the impact of this change from Area Deprivation Index to Community Deprivation Index, identifying heterogeneous effects across different populations. Importantly, our work has also uncovered additional elements that could be optimized to further improve the approach to social risk adjustment.

Calibrate risk adjustment on health, rather than spending, outcomes

Traditionally, risk adjustment examines historical spending patterns to predict future spending and set payments accordingly. This focus on spending would seem appropriate under a goal of leveling the financial playing field for healthcare organizations participating in a payment model, as well as a prevailing presumption is that high-needs populations require more healthcare and incur greater spending. Yet there is evidence that spending may be paradoxically lower for high-needs populations, because those populations lack adequate access to healthcare services and therefore do not incur spending. Risk adjustment may then underestimate the true health needs of the most disadvantaged populations. These dynamics highlight the problematic nature of risk adjustment focused solely on costs—namely, the risk for unintended consequences stemming from the fact that costs are conflated by access issues.

A truly equity-driven approach would calibrate social risk adjustment based on health outcomes, such as mortality, rather than spending. Of course, overhauling existing risk adjustment approaches would be no small feat, and focusing on rare outcomes like mortality would introduce other methodological challenges. Yet as our research suggests, policymakers have an opportunity to direct social risk adjustment policies toward their intended outcome: to aid clinicians and organizations caring for populations in which social factors driven worse clinical outcomes.

Assess individual risk, rather than area-level

Social risk adjustment currently relies on area-level indices for socioeconomic disadvantage, like the CDI. The reason is related to data availability: detailed patient-level information on health-related social needs is often unavailable or incomplete in claims data, and therefore measures tied to geography may be the best proxy for individual social needs. Our work to date has confirmed that indices like CDI are correlated with individual patient outcomes, even after adjusting for clinical risk. Yet future approaches to social risk adjustment may calibrate risk based on individual factors, should that data eventually become available, to improve the precision with which risk adjustment can allocate financial resources.

Determining the ‘right’ payments

Our research underscores that an important policy question is the magnitude of dollars in question, both those provided additionally to or clawed back from clinicians and organizations in payment models, when considering social factors. In an ideal world, additional payments available through social risk adjustment would be sufficient to allow safety-net organizations and other groups serving disadvantaged populations to make innovative decisions or investments that improve outcomes and reduce spending. While pragmatic constraints exist (e.g., budget neutrality, cost-efficiency goals), the dollars available for social risk adjustment should be enough to both encourage safety-net organizations to participate and afford them the financial flexibility to make meaningful improvements.

Optimize transparency and simplicity

To use funds from social risk adjustment well, clinicians and delivery organizations would benefit from advanced knowledge about the dollars that will be available to them. Unfortunately, risk adjustment can be an opaque process, with targets established through complicated formulas with data that may not be available or usable, particularly by safety-net organizations with already limited resources. Furthermore, incentives and penalties may be distributed or reclaimed after the fact through “retrospective reconciliation”, leaving organizations unable to fully anticipate how to use social risk adjustment dollars, much less how they will perform in a payment model. An equity-driven approach would seek to optimize transparency and simplicity, allowing clinicians and organizations to estimate how well they would perform specifically for their populations.

Conclusions

The arguments for including social risk adjustment in value-based payment are strong. Yet, as suggested by our research to date, improvements are needed to reach optimal approaches for doing so. In ongoing research supported by the Donaghue Foundation, we plan to continue exploring important questions in this direction in the hopes of guiding policymakers toward the best possible version of this important tool.

Back Issues

Developing a Research Agenda on High-Value, Equitable Care: The Power of Being Practical, Inclusive, and Innovative

The Room Where Research Happens: How I Became Part of a Group that Was Open to Research the Topic that Few Seemed Willing to Discuss